Discover posts

Till we have faces covered part 4

How can we have self-knowledge, and cultivate it in the young as well, if we have faces covered? Perhaps the most poignant answer to this question lies in C. S. Lewis's final novel, Till We Have Faces. Having gone most of her life hiding her face in a white veil, Orual comes to the end of her life and finds her complaint against the gods answered in a surprising way. She assumes she knows herself and others in her life with an almost infallible knowledge. But she is shocked to find herself in a vision standing before the court of the gods, stripped of both her veil and of the speech for which she had been preparing all her life. "The complaint was the answer," Orual tells us, "To have heard myself making it was to be answered" (305).

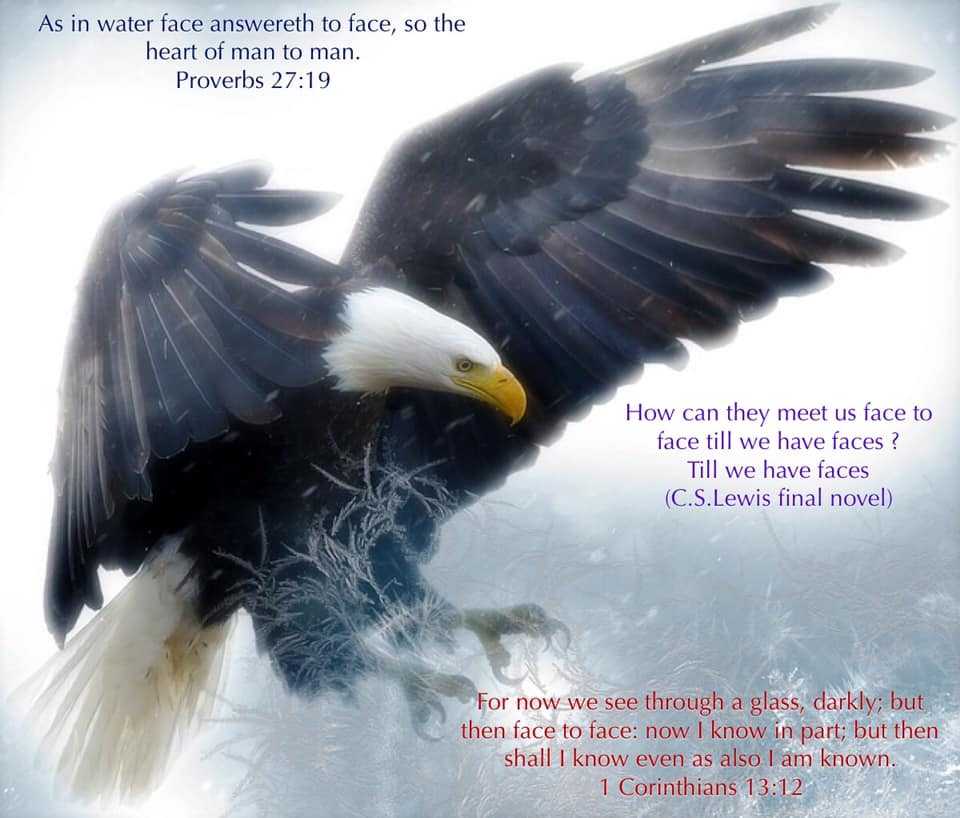

This is that same reciprocal law that Roger Scruton says operates within the healthy human relationships where true self-knowledge is revealed in the sacred countenance of the other. "I saw well why the gods do not speak to us openly," says Orual, "nor let us answer. Till that word can be dug out of us, why should they hear the babble that we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?" Aside from this being one of the finest lines in English prose, Lewis is so instructive here. The metonymy of the face stands not merely for that embodied "speech" which lies at the very center of our being but for our very identity. The human face is how we are known and in the gaze of others how we know ourselves.

What of that child I observed gazing at her mother? How will this affect her social development, her own psychological well-being, or her emotional competence? "True goodness, simplicity, and kindness cannot so be hidden," says Marcus Aurelius, writing in the second century. "In the very eyes and countenance they will show themselves." And in contemplating the face of her mother, was the child not also contemplating her own being as well? And if the face conveys some knowledge of our identity, then it must also convey some knowledge of the origin from which that identity comes.

Covering the face, then, is to obscure the loudest and most communicative aspect of the image of God. It is literally an icon. If this is the cost for wearing the damn mask, then it is a heavy one indeed. For the game of peek-a-boo continues with no end in sight.

Devin O'Donnell is the author of The Age of Martha, a book on leisure and education (Classical Academic Press, 2019). He served as Research Editor of Bibliotheca and has taught literature for 15 years. He writes for the CiRCE Institute blog and is currently Headmaster of St. Abraham's Classical Christian Academy. He is a classical hack, who came up through the manhole covers of learned society to find wisdom.

This article is from Touchstone Magazine

A Journal of Mere Christianity

Touchstone is a Christian journal, conservative in doctrine and eclectic in content, with editors and readers from each of the three great divisions of Christendom—Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox.

Till we have faces covered Part 3

The human face communicates; it conveys an anthropological type of knowledge. When, for instance, Lady Capulet tries to convince young Juliet that Paris is a worthy match, she enjoins her daughter to behold the good things written in his face: "Read o'er the volume of young Paris' face, / And find delight writ there with beauty's pen." In Coriolanus, Menenius tells the envious tribunes, "You know neither me, yourselves nor any thing," which he indicates is linked to their duplicity: "you make faces like mummers." The insult is that they are mere actors of virtue.

Alternatively, in Henry IV, Part I, had Harry Hotspur only worn a face mask, he could perhaps have concealed his consternation from his wife. But the face is its own world, and just as one reads the storm in oncoming clouds, Lady Percy sees in the microcosm of Harry's countenance "portents" that "strange motions have appear'd, / Such as we see when men restrain their breath / On some great sudden hest." And in Much Ado About Nothing, when Hero is falsely accused of infidelity, Friar Francis needs only to examine her appearance to discover "A thousand blushing apparitions / To start into her face," and that "a thousand innocent shames / In angel whiteness beat away those blushes." It is in looking into her face that the Friar finds her blush to be the symbol of her innocent "fire," which eventually burns "the errors that these princes hold against her maiden truth."

What Shakespeare shows, Solomon plainly tells: "As in water face answereth to face, so the heart of man to man" (Prov. 27:19). The principle is simple, yet so foundational for the virtue of friendship. Because the face is by its nature linguistic, it thus conveys a knowledge not only of the other but also of the self.

How is this so? In How to Be a Conservative, Roger Scruton explains, "The other's face is a mirror in which they see their own. Precisely because attention is fixed on the other, there is an opportunity for self-knowledge and self-discovery" (148). This is how friendship is built. "In the once normal conditions of human contact, people became friends by being in each other's presence." It wasn't simply the "information" of verbal signals that was communicated. "Attention," writes Scruton, "was fixed on the other's face, words and gestures. And his or her nature as an embodied person was the focus of the friendly feelings that he or she inspired."

What this ultimately means is that human relations are altered without face-to-face encounters. When we do encounter each other in, say, the tête-à-tête, one of the bases of Western civilization is preserved. Scruton continues, "The object of friendly feelings looks back at you, and freely responds to your free activity, amplifying both your awareness and his own. In short, friendship, as traditionally conceived, was a route to self-knowledge" (148).

- The Heavy Cost of Covering

Till we have faces covered Part 2

Given the rising obligations and popularity of face masks in our current moment, a bit of marshwigglian pessimism is useful. Again, it's not about the effectiveness or "science" of face masks. The concern lies in the unscrupulous enthusiasm that attends the advocacy of face coverings. There is an anthropological cost. And this, I argue, is especially important for children, whose education as human beings made in the image of God depends on the ability to see the human face and to be seen by it.

I have heard elementary school teachers, for instance, raise objections over face coverings for children. But these objections come mainly in two forms: the complaints about having to police kids over face masks in the classroom, and the practical challenges face coverings will have on teaching method and pedagogy. They are not wrong, of course. After all, how can anyone teach grammar or phonemes, language or phonics with something like the "Minister's Black Veil" eclipsing the face? An obvious problem and a good question. But it is not the only problem. Nor is it the only question to consider.

We need to ask what the human countenance means. This seems to me what the critics of the anti-maskers seem to miss. They judge those who are reluctant to wear the mask as merely being obstinate and zealous for their rights. But what they miss is the more connate spiritual reason why hiding the face feels so damaging to one's personhood. What they mistake for pettiness or stubborn pride in others less willing to cover up is perhaps much more humane than expected. And what they take for virtues of magnanimity or scientific wokeness may actually be just plain old condescending arrogance. There may be a deeper reason why people resist face coverings, regardless of one's sensitivity to Covid or how one feels we ought to respond.

- A Conveyer of Knowledge

TIP: As this platform only has 3 visibility settings

(Everyone, Friends, Only Me)

if you want to interact with people without laying bare your whole life,

try creating a page, group, or topic in the forum.

GROUPS can be set to private/invite only.

Don't forget to change the privacy settings on your posts

if you don't want everyone to see them!